A curriculum is a group of related courses, often in a special field of study. Or, stated in a more formal term: a planned educational experience (Brock, 2009). When developing a curriculum there are some general assumptions:

- Educational programmes have aims and goals, even when they are not clearly articulated

- A systematic approach to curriculum development will help achieve these aims and goals

- Educators have the ethical obligation to meet the needs of their learners

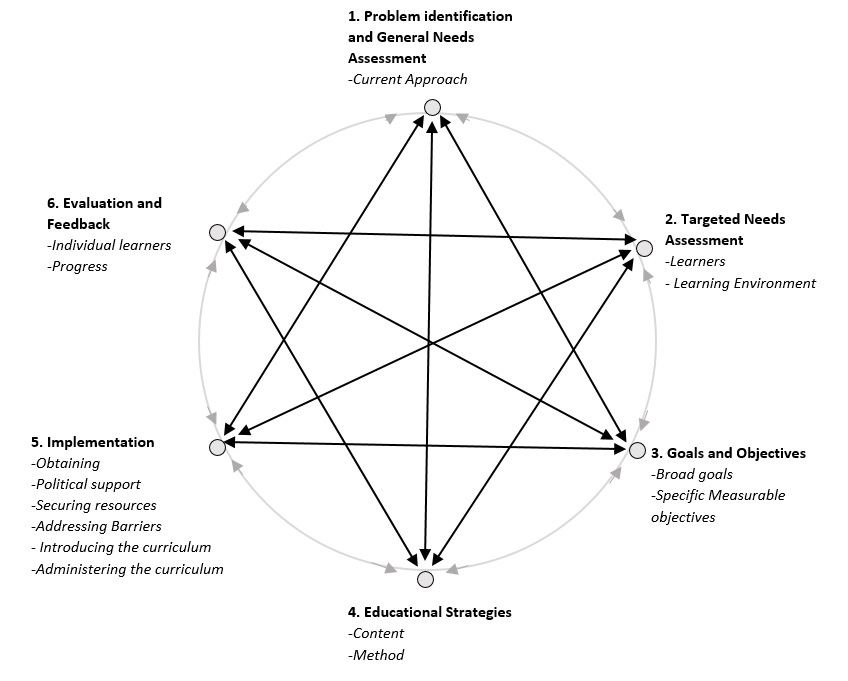

Curriculum development determines the type of information that is taught, as well as how it will be taught, and who will teach it. It is an iterative process based on a six-step approach. These six steps will be discussed next.

Getting started

Step 1 Problem identification and general needs assessment

The need for curriculum development usually emerges from a concern about a major issue or problem of one or more target audience. The first step explores some of the questions that need to be addressed to define the issue and to develop a statement that will guide the selection of the members of a curriculum development team. The issue statement also serves to broadly identify the scope (what will be included) of the curriculum content.

Step 2 Needs assessment for targeted learners

A needs assessment of targeted learners is a process by which the curriculum developers identify the differences between the ideal and actual characteristics of the targeted learner group and their environment. Some methods to conduct a need analysis are:

- Formal interviews

- Focus group discussions

- Questionnaires

- Audits of current performance

Step 3 Goals and objectives

After the needs of learners have been clarified, the curriculum is targeted to address these needs by setting goals and objectives. A goal or objective is defined as an end towards which an effort is directed.

A goal is a broad educational objective or directive. It communicates the overall purposes of the curriculum. An objective is a more specific educational directive that is usually stated behaviorally, i.e. it is measurable.

Step 4 Educational strategies

Once the goals and objectives are determined, the next step is to develop educational strategies. There is a distinction between content, specific material to be included in the curriculum, and methods and ways in which content is presented.

Step 5 Implementation

Within implementation a major part concerns determination of available resources:

- Personnel: teaching staff / secretarial / administrative support

- Time: teaching staff , support staff, learners

- Facilities: space, equipment, IT

- Funding/costs: direct financial costs, hidden or opportunity costs

Step 6 Evaluation and feedback

Step 6 closes the loop in the curriculum development cycle and provides information to guide individuals and the curriculum in cycles of improvement. Evaluation results can be used to seek support for curriculum, assess individual achievement and satisfy external requirements.

Further reading

- Brock, S. J., Rovegno, I., & Oliver, K. L. (2009). The influence of student status on student interactions and experiences during a sport education unit. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 14(4), 355-375.

- Read more about the six-step approach in: Kern, D. E. (2015). Overview: A six-step approach to curriculum development. In Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach, Third Edition (pp. 5-10). Johns Hopkins University Press.

- A handbook on curriculum development